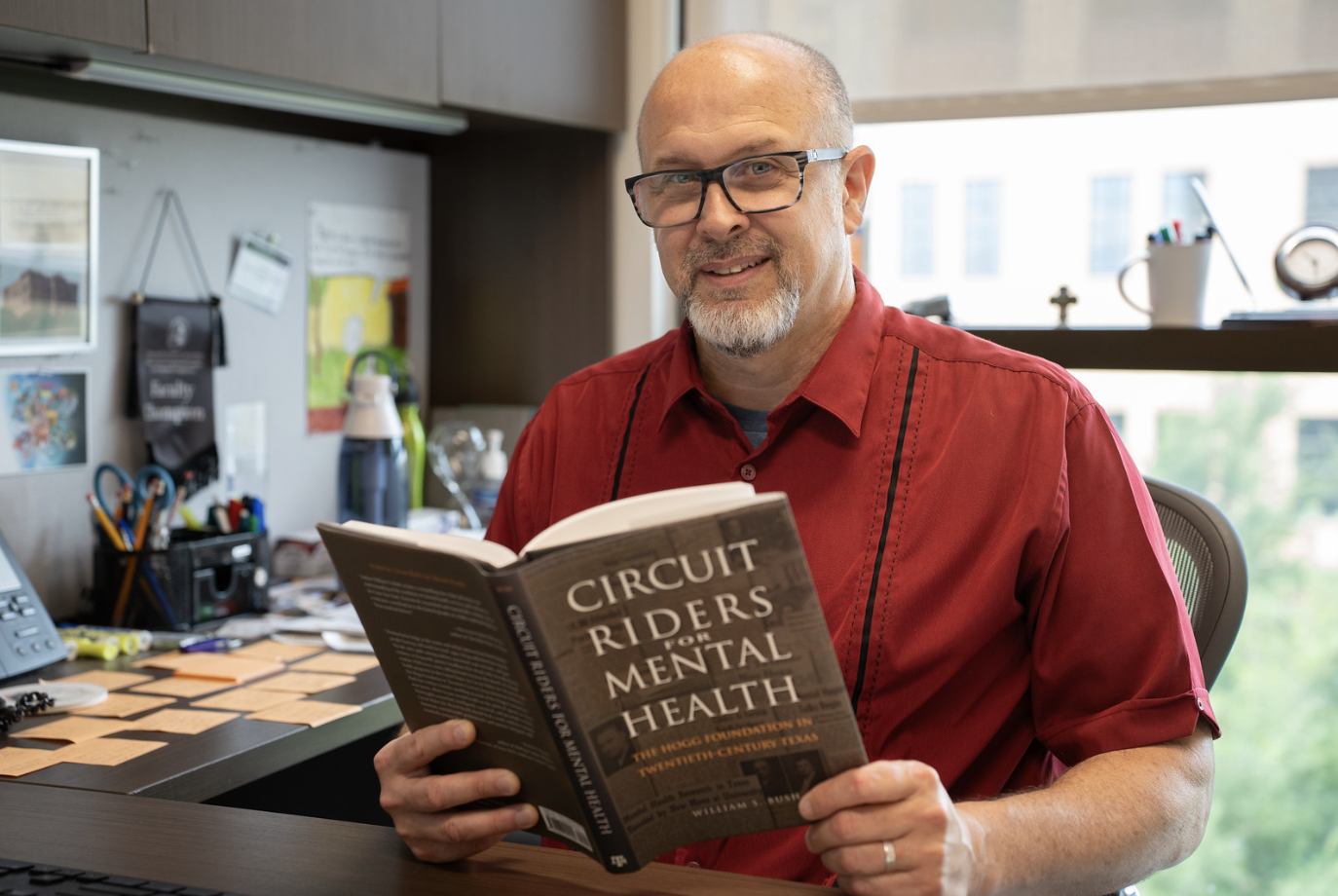

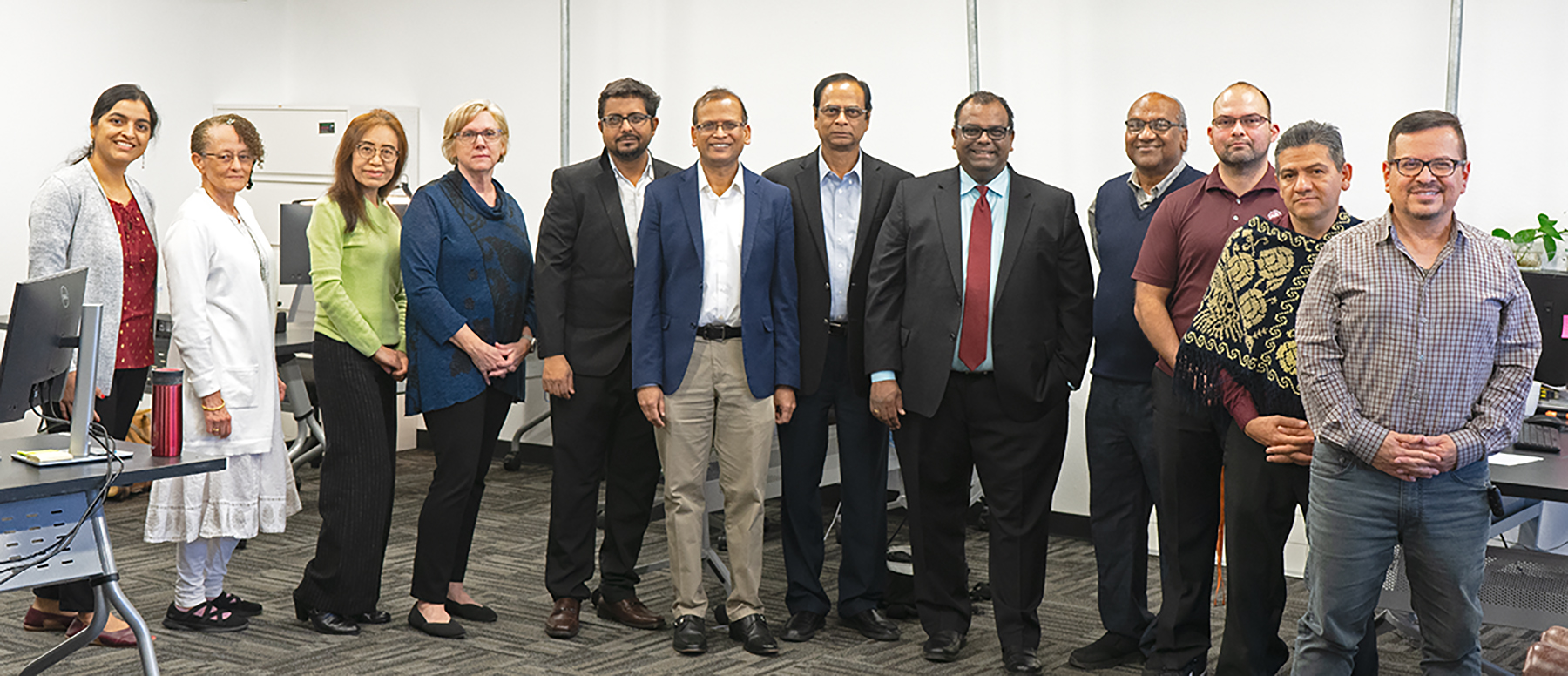

Faculty members from across A&M-San Antonio (including Dr. Bryan Bayles, pictured above) reflect on what sustainability means to them within the context of their academic disciplines.

Today sustainability encompasses a broad scope of interests and activities, including clean energy, biodiversity, environmental and social justice, DEI, and mental and physical well-being, among other priorities. A&M-SA Today recently tapped faculty members from across disciplines to articulate what sustainability means to them with regard to their specific research and scholarship activity and the course content they teach, as well as what sustainability means to them personally. What follows are highlights of their reflections.

Dr. Bryan Bayles, Research Assistant Professor of Public Health, Department of Life Sciences

As both a medical anthropologist and public health professional, sustainability is at the very core of my academic discipline and life. Both personally and professionally, I like to think of sustainability as the ability to meet our own needs without compromising the ability of future generations to meet theirs. This means mindful attention not just to our own individual physical and emotional wellness, but careful and deliberate use of natural, social, and economic resources such that future generations can enjoy their own optimal physical and emotional wellness.

Public health is the science of protecting and improving the health, well-being, and happiness of populations, whether it be at the neighborhood level or the global level. We do this by promoting healthy lifestyles, researching chronic disease and injury prevention, and detecting, preventing, and responding to infectious diseases. In contrast to clinical professionals like doctors and nurses, who focus primarily on treating individuals after they become sick or injured, public health professionals’ attention is on prevention (and mitigation if prevention is not possible).

One dire threat to sustainability now manifesting before us is climate change. In my own teaching of epidemiology, there are a wide range of climate-sensitive health risks addressed. These include injuries and deaths from extreme weather events (e.g., heat waves, floods, droughts, wildfires, storms), emerging infectious diseases (including food-, water-, and vector-borne illnesses), and water and food insecurity, as well as diseases caused by poor air and water quality.

Proactive and creative action is urgently needed not only by public health professionals, but by “upstream” sectors that contribute mightily to the likelihood of a sustainable and resilient future. This includes the agriculture, energy, transportation, health-care and water industries. As public health practitioners, we increasingly find ourselves working in interdisciplinary teams together with biologists, chemists, engineers, data scientists, and many others to tackle these challenges.

Employing an equity lens in public health is critical to achieve meaningful sustainability. Both infectious and non-communicable diseases and risks affect the poorest and most vulnerable marginalized populations among us at disproportionate rates. The COVID-19 pandemic, while itself an infectious disease, has highlighted longstanding and deep disparities in underlying chronic diseases, such as Type 2 diabetes, obesity, hypertension, stress, and heart disease. It has also highlighted the central role that “Social Determinants of Health” play in morbidity and mortality.

The conditions where we live, learn, work, and play affect a wide range of health and quality-of life-risks and outcomes. Access to safe, clean air and water, affordable housing, education, reliable transportation, living wages and paid sick leave, health insurance, as well as social cohesion and support are all critical elements of public health. Designing, implementing, and evaluating programs to decrease health inequities is what drives my professional research agenda.

Whether I am researching COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy, post-traumatic injury among youth or veterans, or working with clinicians to prevent illnesses caused by exposures to toxic chemicals, the theme of health equity remains my North Star for research and action. At the center of my research is always the question: How can we create empathetic, scientifically informed, and effective responses that lead to a healthier, happier, and more sustainable future for all?

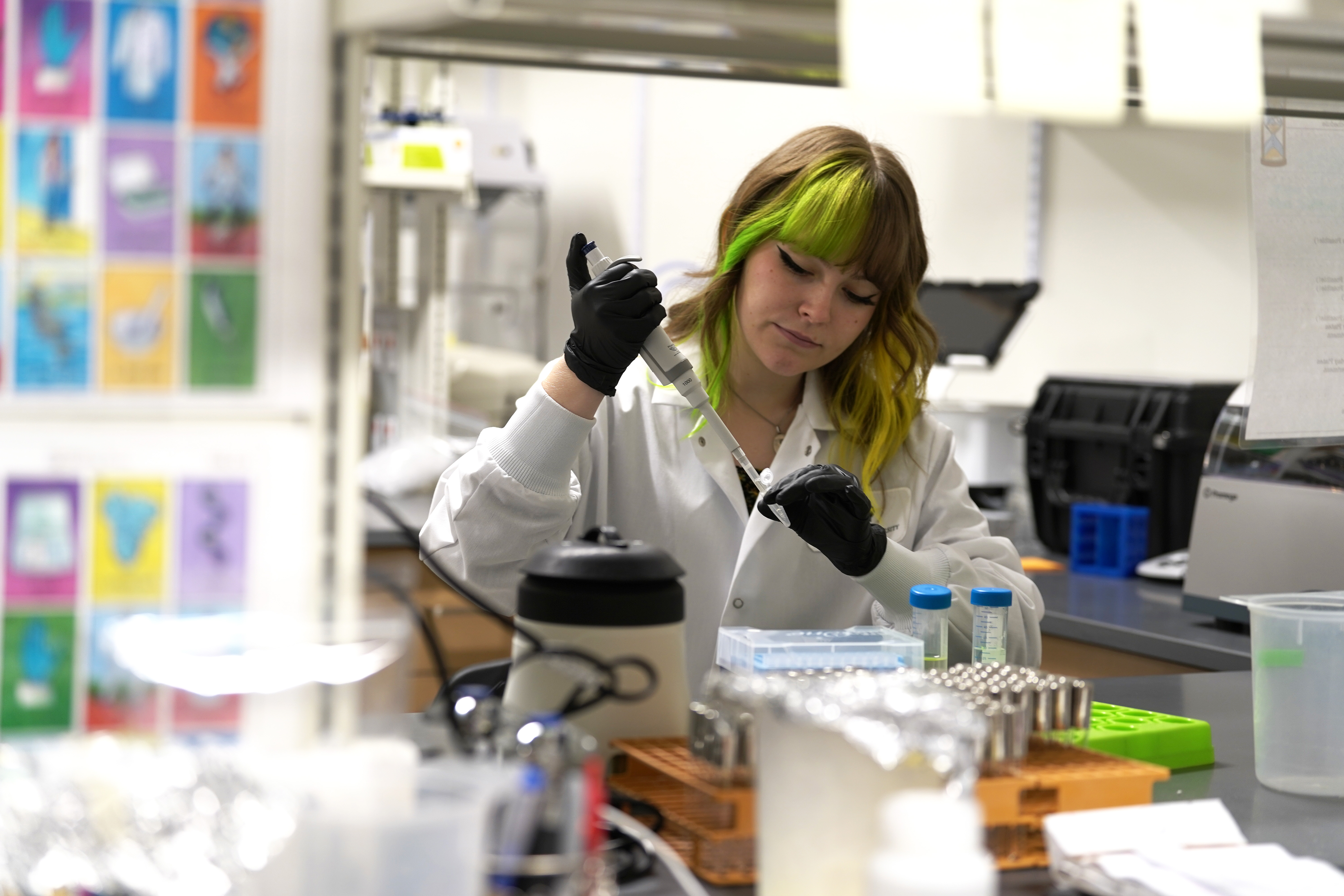

Dr. Davida S. Smyth, Associate Professor of Molecular Microbiology, Department of Life Sciences

Sustainability means choosing to conduct my research in a way that is mindful of waste and environmental impacts in all their forms, and of the impact that waste has on planetary health. Sustainability is a mentality and philosophy that, once you’ve adopted, is hard not to integrate throughout your day-to-day life. We are only renting the earth for our lifetimes, and we should treat it with respect, love, and attention.

(Editor’s note: Read a recent article Dr. Smyth co-wrote on single-use plastic in the journal Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development: “The Sustainability Challenges Facing Research and Teaching Laboratories When Going Green.”)

Dr. Walter Den, Professor of Water Resources Science and Technology, Department of Mathematical, Physical, and Engineering Sciences

My academic discipline falls nicely in the environmental sustainability area. Admittedly as an engineer by training, systematically compartmentalizing complex problems (of which sustainability certainly is one) makes it easier for me to simplify the problem. So, my focus on environmental sustainability recognizes that economic sustainability and social sustainability are interlinked with environmental sustainability.

In a narrow sense, environmental sustainability means that we “sustainably” consume things at a rate equal to or slower than nature can produce them. This principle applies to all natural resources—whether it be water, minerals, energy, metals, and so forth—and suggests that consumable products that cannot be reduced to their natural forms are not sustainable. Think plastics. Think non-sticking films. The production process also needs to be in a “closed loop” that must be zero carbon and zero discharge, and all materials must be recyclable and not fall out of the loop.

With regard to sustainable water uses and policies, one question becomes how the industrial, commercial, and agricultural sectors can use water responsibly and how technologies can help achieve these goals.

Another concern is the nexus of water, food, and energy. From local to global lenses, these three essential elements of life interconnect with each other, so how can we avoid overly tilting in favor of one or two elements while overlooking the other?

Sustainability means survival; it means changing of one’s lifestyle; it means awareness; it means conservation. It also means sustained leadership and policies.

Amid all these priorities, it’s important to recognize that there will be no sustainability without profitability, and there will be no profitability without sustainability. In the world we live in, profitability drives innovation and innovation rewards profits, and that is likewise true for innovation in sustainable products, processes, and policies.

Dr. Weixing Ford, Assistant Professor, Department of Marketing and Management

In business, sustainability means that a business enterprise has positive rather than negative impact on its community and environment locally and globally. Going “green” is becoming an important part of corporate social responsibility. Consumers often favor the brands or businesses that operate in a sustainable manner.

Although a sustainability goal is highly desirable by all kinds of business enterprises, it is usually costly to strive for sustainability. In my class, students enthusiastically engage in discussions on how to run a business sustainably while still maintaining competitive edge, such as how to make better use of the massive returned merchandise rather than send these items to the landfill, which is too often the case for some businesses. In my research, I studied how the subtle message in advertisement may help put consumers in a more “green” mindset. On a personal level, being “green” is an important part of my identity, and I take pride in my efforts of preserving the environment and contributing to my community through my lifestyle and conscientious consumption. More importantly, I would like to utilize my educator’s role to influence others through my teaching and my research to adopt a sustainability mindset, and to help others cultivate their green actions and choices.